For at least 30 years, the container shipping industry has been locked in a frequent boom and bust round. During the tough growth of macroeconomic, containing shipping fees would increase, and operators of container ships would reinvest their earnings in new-ever bigger ships. Then the economy would go down into a downturn, demand would fall, rates would fall over, and container ship operators would find themselves loaded with heavy debt as well as idle ships. As overfilling kept a tight lid on rate, leverage would get bigger; profits would fall as well as container ship operators would fall into bankruptcy or be kept out of court, thanks to amending and extended deals with their creditors.

On the other hand, at this point, the basics which would back an escape from that cycle are in place

The container shipping business is experiencing a boom phase, with the worldwide container shipping rate indexes to USD5 000 for every 40-foot container in February this year after going up steadily and steeply since 2020 May. Today, with some prominent and famous exceptions, freight carriers are not yet flooding the international shipyards with orders. Rather, they need to successfully manage capacity, keep prices stable as they need to slip by 5 percent during the month of January to September 2020 while general capacity is boosted by only 2 percent. In the meantime, an idle capacity that increased to 11 percent in 2020 May, moved back to 3 percent by the 3rd quarter of the year due to the increased blank sailing in the industry as well as suspended service on several routes due to a pandemic and freight carriers cut sailing speeds that go down to 1.8 percent in the year 2020.

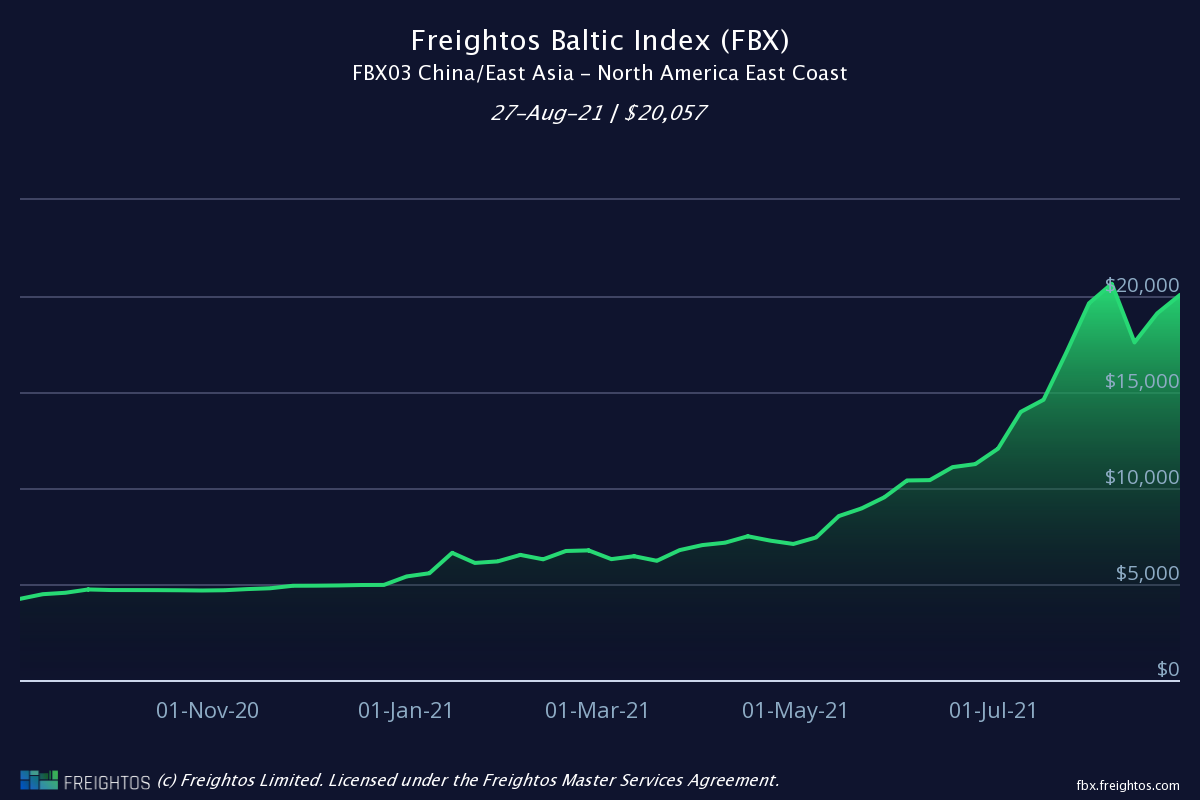

The container shipping market is currently experiencing a recovery phase. Global container shipping indices have been hitting records since May 2020. The cost of transporting 1 TEU in some directions from Asia for September 2021 exceeds USD20 000. Just take a look at Baltic Container Shipping Index

This is due to the fact that during the pandemic, the demand for goods, therefore, for the freight of ships fell. Shipping companies began to put vessels on storage in order to minimize transport costs. This was followed by an explosive growth in demand, and it takes time to reopen. Trade chains were also rebuilt, there was a problem with a shortage of containers in one port and an excess in another. This is what explains the skyrocketing prices for container shipments from China.

Activities like mergers and acquisitions keep on apace, furthering the consolidation in the container shipping industry; now, seven international carriers control 5 percent market share, and three coalitions have assisted increase rating leverage. The cost of fuel stays low despite strict new rules intended to reduce the emissions of sulfur as an introduction to additional measures made to decarbonize the container shipping industry. One impact of the new rules is the limitation on capacity growth.

A sustainable exit from boom and bust, on the other hand, needs freight carriers to work out discipline over their rating and order books because the rates make their inevitable and eventual regression to the mean- discipline which carriers previously had fast to discard when earnings were rising. In an indication that such discipline might already be fraying, recently, many freight carriers have placed big orders for new ships. However, further inclusion of fleet capacity could seriously dilute any rating power which freight carriers can establish.

History Repeat Itself

The industry of container shipping has long followed a different pattern. Think of the industry’s actions during the downturn years of 2001 up to 2003, and the succeeding economic recuperation and improvement. The downturn brought on by the exploding of the initial dot-com bubble resulted in an immediate drop-off in demand, followed by a long spell of low rates in shipping. Vessels ordered when periods were good, beginning in 1999 and the early quarter of 2021, before the bubble bursting- were shipped just as demand and fees declined.

The latest builds drove up ship overcapacity that got aggravated as shippers kept their records low relative to sales. The container shipping business has become very fragmented without coalitions of ship liner owners forming to improve supply-side pricing power. The cost of fuel was low; however, it just provided limited relief to container carriers, whose big problems were the common ones of overcapacity and too little order.

History repeated itself in respect to the year 2009 to the year 2015. In the year 2009, after many years of increasing rates, capacity, and profits, the Great Recession happened, and demand catered. Fees or rates sunk by over 50 percent in the year 2009 and then, next to a short bounce back, once more dropped by 50 percent when an upturn failed to be set in the year 2010. Even if container shipping operators and owners idled 10 percent of their fleets and lessened sailing speeds, those actions came too late to defy the record-setting capacity increase of 2004 and 2008. Many shipping lines went under or acquired in the outcome- portion of a consolidation wave presented in the year 2013, which left the best and renowned carriers in control of almost 46 percent of international 20-foot equivalent units, or also known as TEUs, and in many years, assured better capacity control. Despite signs that a diverse dynamic today prevails in the shipping industry, freight carriers could cast away capacity discipline and pricing at any time they think doing so will serve their wants and interests. It has occurred in the past. For example, in 2014, the shipping industry was put on the edge of going to a time of sustained capacity control and consolidation. On the other hand, soon after some freight carriers decided to place orders for new ships, the rest of the shipping industry followed suit, bringing about the boom and bust cycle.

Will Freight Carriers Seize the Opportunity?

A lot of freight carriers at this point are exercising self-control in the face of enhancing market basics. Few of the most compelling proof of a significant change in the shipping business dynamic is found in the newest statistic on shipping capacity, which before. Demands astound hit only as orders for new ships were growing or already at a high level- in the newest cycle, an immediate decrease in demand happened while both orders for new ships and capacity were quite low.

Unlike during past need disturbances, shipping values have held up, even if existing levers are surely unsustainable. Shipping rates dropped considerably from the year 2001 up to the 2003 recession before bouncing back steadily during the upturn. The following recession was marked by unceasingly low rates, relatively shallow, interrupted by two spikes. The existing cycle is noticed by a good increase that started in the first four months of 2020 and continued into the first four months of 2021.

Restrained development in the supply of vessels goes a long way to explaining the preferred rate setting. In past cycles, the shipping industry was aggressively putting to capacity when need dried up, this making an excess supply that took many months to work off. In contrast, in the existing cycle, the shipping industry was cutting capacity when the worldwide health crisis or COVID-19 slammed the brakes on the international economy, having started a time of intensive vessel demolitions in 2009, which persisted through the year 2018.

At this point, orders for the latest ships stand at a historical low. Even if many carriers put big orders for a new ship in the past, it will take many years to put back the tonnage which was knocked down. There is an improvement in the management of the capacity as carriers have improved blank sailings, lessened speeds, and suspended service on some destinations or routes.

At this point, orders for the latest ships stand at a historical low. Even if many carriers put big orders for a new ship in the past, it will take many years to put back the tonnage which was knocked down. There is an improvement in the management of the capacity as carriers have improved blank sailings, lessened speeds, and suspended service on some destinations or routes.

The level of frustration amongst shippers is that they’re ready to take the step and make far-reaching amendments to their transport plan, although they involve extra, unplanned assets. They could help the development of market transporters through less international, more regional freight flow management, at least until assurance from the renowned shipping companies has been reinstated.